Image via Warner Bros.

Image via Warner Bros.Jeremy has more than 2200 published articles on Collider to his name, and has been writing for the site since February 2022. He's an omnivore when it comes to his movie-watching diet, so will gladly watch and write about almost anything, from old Godzilla films to gangster flicks to samurai movies to classic musicals to the French New Wave to the MCU... well, maybe not the Disney+ shows.

His favorite directors include Martin Scorsese, Sergio Leone, Akira Kurosawa, Quentin Tarantino, Werner Herzog, John Woo, Bob Fosse, Fritz Lang, Guillermo del Toro, and Yoji Yamada. He's also very proud of the fact that he's seen every single Nicolas Cage movie released before 2022, even though doing so often felt like a tremendous waste of time. He's plagued by the question of whether or not The Room is genuinely terrible or some kind of accidental masterpiece, and has been for more than 12 years (and a similar number of viewings).

When he's not writing lists - and the occasional feature article - for Collider, he also likes to upload film reviews to his Letterboxd profile (username: Jeremy Urquhart) and Instagram account.

He has achieved his 2025 goal of reading all 13,467 novels written by Stephen King, and plans to spend the next year or two getting through the author's 82,756 short stories and 105,433 novellas.

Sign in to your Collider account

Instead of being a direct sequel, in the way Toy Story 2 is an unambiguous follow-up to Toy Story, a spiritual sequel is one where the story from the first isn't directly continued, but things feel thematically or stylistically linked. If there are any directly recurring plot threads, or characters who play roles in both, then it’s going to be a sequel in the traditional sense, rather than a spiritual one.

In that way, a spiritual sequel might also be called a thematic sequel, or just indicate a filmmaker wanting to say a little more about a movie they (or someone else) might've directed. With the following examples, most are instances where one director made two films that have similarities of the non-direct kind, but there are a couple of spiritual sequels (perhaps even less direct ones) below as well, to keep things a little more interesting.

10 'Carlito's Way' (1993)

To 'Scarface' (1983)

Image via Universal Pictures

Image via Universal PicturesScarface might not be the best Al Pacino movie, though it’s potentially a contender, and it could likely be called the most over-the-top Al Pacino movie. The bombast and in-your-face style are hard to deny, and it’s a highlight within the filmography of Brian De Palma, too, not to mention one of the very best remakes in cinema history (the 1930s Scarface was good for its time, of course, but 1983’s Scarface is next-level).

10 years on from Scarface, De Palma and Pacino re-teamed to make Carlito’s Way, and it was a good deal more subdued and somber. Both films are about crime, but one has Al Pacino playing the lead role in a rise-and-fall kind of story, while the other has him playing a character trying – and struggling – to seek redemption, and move on from his life of crime, rather than getting continually more wrapped up in such a lifestyle. They're also both rather tragic films, but in very different ways.

9 'Only God Forgives' (2013)

To 'Drive' (2011)

Image via Film District

Image via Film DistrictJust two years on from Drive, director Nicholas Winding Refn and lead actor Ryan Gosling re-teamed to make something that was almost a sequel to their 2011 movie: Only God Forgives. It’s got the slow pacing, intense violence, undeniable style (perhaps even over substance), and a certain detached quality that feels very in line with certain strains of arthouse cinema.

But it’s really not a sequel. Gosling’s a different character, there’s not really anything as universally appealing as the love story side of things in Drive, and no characters from one show up in the other. Only God Forgives isn't quite as good, either, but it’s a bit better than some give it credit for being, and some of the backlash, at the time, may well have been that it only scratched some of the same itches that Drive did (and not everyone loved Drive in the first place, either).

8 'The Rock' (1996)

To Sean Connery's 'James Bond' Movies

Image via Buena Vista Pictures Distribution

Image via Buena Vista Pictures DistributionThis is maybe the biggest stretch of all the examples here, but there is a fun (and, by now, quite well-known) theory regarding The Rock being some sort of stealth sequel to the early James Bond movies with Sean Connery. Connery is hyper-competent and a badass in both, and there’s a good deal of mystery surrounding his character in The Rock, so it’s a bit like, why not believe?

Or if you don’t believe in it, then The Rock is still pretty great, and one of the better bombastic and high-concept action movies of its era. The extravagant action and Connery’s coolness in the face of danger are probably the only two things beyond the fan theory side of it all that tie The Rock to any of the early James Bond movies, but it’s still a neat enough example to include here.

7 'Snatch' (2001)

To 'Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels' (1998)

Image via Columbia Pictures

Image via Columbia PicturesMaybe Guy Ritchie peaked early, seeing as his first two films, Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels and Snatch, are probably his best, but they are both very well-paced gangster movies with quite generous amounts of dark comedy. The worst thing you could say about Snatch, criticism-wise, is that it’s probably a little too similar to Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels.

But if your movie’s similar to a very good movie, and your movie’s still very good, then that mitigates the whole point of criticism quite a bit. Anyway, Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels and Snatch both have large ensemble casts (including some shared actors), a similar pace, surprising scenes of violence and plot twists, and comparable stylistic touches. Snatch doesn’t directly continue the first Ritchie-directed film in a narrative sense, but it does function as a remix of sorts, revisiting lots of things that made Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels good to begin with.

6 'Waterloo' (1970)

To 'War and Peace' (1965-1967)

My my. So, in War and Peace, the war everything’s centered around is the Napoleonic one, but Napoleon Bonaparte himself isn't really a big character or anything, just seen occasionally and obviously a big factor in why so much of the drama happens. It’s a remarkable epic, the four-part adaptation directed by Sergei Bondarchuk, and the director tackled another film afterward that was more Napoleon-centric.

That film was the appropriately titled Waterloo, and though the parts of it that don’t showcase large-scale battles aren’t quite as interesting as the comparable sequences in War and Peace, both movies do excel when it comes to showing large-scale conflict. And since the Battle of Waterloo was the one that brought about the end of the Napoleonic Wars, it feels fitting to watch a movie all about it following War and Peace.

5 'Fallen Angels' (1995)

To 'Chungking Express' (1994)

Image via Jet Tone Productions

Image via Jet Tone ProductionsIf you watched Chungking Express and then immediately dove into Fallen Angels, you might well feel like you’ve watched one giant film, or maybe even a trilogy. There are two stories told in Chungking Express, with the film being split into two halves quite neatly (and even abruptly), and then two stories told in Fallen Angels, too, but they're intertwined in this instance, which is why Fallen Angels might feel like an extended third part to that previously suggested “trilogy.”

Both films, and all the stories contained within, explore similar themes and are also in line emotionally and visually, with the struggles of love and finding connection being covered throughout. Fallen Angels is a bit more chaotic, challenging, and ultimately darker, though, even if it remains likely that, if you enjoyed Chungking Express, you'll probably find at least a little to appreciate in Fallen Angels.

4 'Samurai Rebellion' (1967)

To 'Harakiri' (1962)

Image via Toho

Image via TohoIt’s best to space out watching both Harakiri and Samurai Rebellion. They should ultimately both be watched, if you’re a fan of samurai movies and somehow haven’t seen either yet, but both of these Masaki Kobayashi-directed films are harrowing affairs that are almost like anti-samurai movies, since they dive into critiquing aspects of the samurai way of life, and also the culture/history that the samurai existed within.

Neither film is particularly action-packed either, by design, though you get a bit of swordplay in each movie, of a sort that’s very vicious by the standards of 1960s cinema. Harakiri is the stronger film overall, so it’s not quite the case that Kobayashi improved upon that sort of samurai movie with Samurai Rebellion, yet it has many of the same strengths as Harakiri, and is still a worthy thematic follow-up/spiritual sequel.

3 'The Irishman' (2019)

To 'Goodfellas' (1990) and Other Martin Scorsese Crime Films

Image via Netflix

Image via NetflixThe thing that might be most special about The Irishman is that it really couldn’t have been made as successfully by a younger filmmaker, so it’s an indication that Martin Scorsese is willing to turn a weakness for some (being an older filmmaker and potentially having less energy) into a strength. Well, The Irishman doesn’t lack energy, as it moves well for a movie of its length, but it is a more downbeat and introspective affair than the other crime movies Scorsese is known for.

Goodfellas and Casino still felt personal, but maybe they had a bit more style and a certain bombast to the dramatic stories they told, while The Irishman is more patient and perhaps more realistic, too. It’s a deeply sad and ultimately mature film, and there is a great deal of thematic weight added not necessarily by comparing it to Scorsese’s older films, but by considering it Scorsese’s probably final – and more introspective/critical – statement on that whole gangster sub-genre.

2 'To Live and Die in L.A.' (1985)

To 'The French Connection' (1971)

Image via MGM/UA Entertainment Co.

Image via MGM/UA Entertainment Co.Since he made a handful of great movies, William Friedkin’s definitive “best” one is a little hard to pick, but it’s safe to assume The French Connection and To Live and Die in L.A. will always be contenders. And the latter does feel like a follow-up to the former, but done in a way that’s distinctively 1980s in style and feel, rather than very late-60s/early-70s New Hollywood in feel, the way the former was.

Both films have incredible car chases, and To Live and Die in L.A. feels successful in escalating the intensity and bleakness found in The French Connection.

Also, The French Connection feels like a defining New York City-set crime movie, and To Live and Die in L.A. shakes up the setting by taking place in… well, you know. Also, both films have incredible car chases, and To Live and Die in L.A. feels successful in escalating the intensity and bleakness found in The French Connection, and upping the stakes and/or overall impact is often something you want out of a sequel, so it’s got that going for it, too.

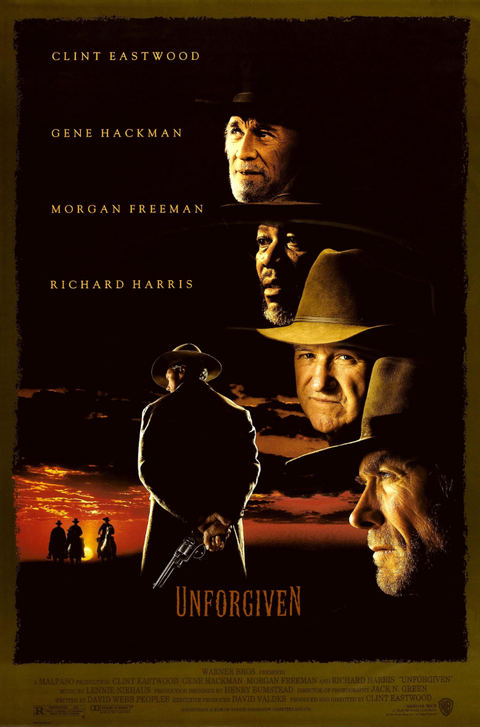

1 'Unforgiven' (1992)

To 'The Dollars Trilogy' (1964-1966)

Image via Warner Bros.

Image via Warner Bros.This one shakes things up a little, compared to most of the aforementioned examples, because Clint Eastwood did not direct the Westerns that Unforgiven feels spiritually in line with. It almost feels like an epilogue of sorts to the films that make up the Dollars Trilogy, which Eastwood starred in early in his acting career, but those movies were directed by Sergio Leone (who, alongside Dirty Harry director Don Siegel, Unforgiven is dedicated to).

Eastwood’s character in Unforgiven, William Munny, is not confirmed to be the Man with No Name, but that man had no name and all, so he might be. Munny’s past is mysterious, beyond the audience being told it was violent, so maybe. It’s more somber and a little slower than the Dollars Trilogy movies, but it feels similarly radical for the Western genre overall, and one does feel Eastwood trying to tap into what made those earlier Westerns so great (and largely succeeding, since Unforgiven is an incredible movie).

Unforgiven

Release Date August 7, 1992

Runtime 130 Mins

Writers David Webb Peoples

.png)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·